Widely acclaimed for his work completing Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time saga, in 2010 Brandon Sanderson began The Stormlight Archive, a grand cycle of his own, one every bit as ambitious and immersive.

Presented here is the story of Kaladin as woven throughout Part One of The Way of Kings, the first volume in this new fantasy series. Take this opportunity to explore Sanderson’s epic in the making.

Roshar is a world of stone and storms. Uncanny tempests of incredible power sweep across the rocky terrain so frequently that they have shaped ecology and civilization alike. Animals hide in shells, trees pull in branches, and grass retracts into the soilless ground. Cities are built only where the topography offers shelter.

It has been centuries since the fall of the ten consecrated orders known as the Knights Radiant, but their Shardblades and Shardplate remain: mystical swords and suits of armor that transform ordinary men into near-invincible warriors. Men trade kingdoms for Shardblades. Wars were fought for them, and won by them.

One such war rages on a ruined landscape called the Shattered Plains. There, Kaladin, who traded his medical apprenticeship for a spear to protect his little brother, has been reduced to slavery. In a war that makes no sense, where ten armies fight separately against a single foe, he struggles to save his men and to fathom the leaders who consider them expendable.

The Way of Kings

“The love of men is a frigid thing, a mountain stream only three steps from the ice. We are his. Oh Stormfather . . . we are his. It is but a thousand days, and the Everstorm comes.”

—Collected on the first day of the week Palah of the month Shash of the year 1171, thirty-one seconds before death. Subject was a darkeyed pregnant woman of middle years. The child did not survive.

Szeth-son-son-Vallano, Truthless of Shinovar, wore white on the day he was to kill a king. The white clothing was a Parshendi tradition, foreign to him. But he did as his masters required and did not ask for an explanation.

He sat in a large stone room, baked by enormous ?repits that cast a garish light upon the revelers, causing beads of sweat to form on their skin as they danced, and drank, and yelled, and sang, and clapped. Some fell to the ground red-faced, the revelry too much for them, their stomachs proving to be inferior wineskins. They looked as if they were dead, at least until their friends carried them out of the feast hall to waiting beds.

Szeth did not sway to the drums, drink the sapphire wine, or stand to dance. He sat on a bench at the back, a still servant in white robes. Few at the treaty-signing celebration noticed him. He was just a servant, and Shin were easy to ignore. Most out here in the East thought Szeth’s kind were docile and harmless. They were generally right.

The drummers began a new rhythm. The beats shook Szeth like a quartet of thumping hearts, pumping waves of invisible blood through the room. Szeth’s masters—who were dismissed as savages by those in more civilized kingdoms—sat at their own tables. They were men with skin of black marbled with red. Parshendi, they were named—cousins to the more docile servant peoples known as parshmen in most of the world. An oddity. They did not call themselves Parshendi; this was the Alethi name for them. It meant, roughly, “parshmen who can think.” Neither side seemed to see that as an insult.

The Parshendi had brought the musicians. At ?rst, the Alethi lighteyes had been hesitant. To them, drums were base instruments of the common, darkeyed people. But wine was the great assassin of both tradition and propriety, and now the Alethi elite danced with abandon.

Szeth stood and began to pick his way through the room. The revelry had lasted long; even the king had retired hours ago. But many still celebrated. As he walked, Szeth was forced to step around Dalinar Kholin—the king’s own brother—who slumped drunken at a small table. The aging but powerfully built man kept waving away those who tried to encourage him to bed. Where was Jasnah, the king’s daughter? Elhokar, the king’s son and heir, sat at the high table, ruling the feast in his father’s absence. He was in conversation with two men, a dark-skinned Azish man who had an odd patch of pale skin on his cheek and a thinner, Alethi-looking man who kept glancing over his shoulder.

The heir’s feasting companions were unimportant. Szeth stayed far from the heir, skirting the sides of the room, passing the drummers. Musicspren zipped through the air around them, the tiny spirits taking the form of spinning translucent ribbons. As Szeth passed the drummers, they noted him. They would withdraw soon, along with all of the other Parshendi.

They did not seem o?ended. They did not seem angry. And yet they were going to break their treaty of only a few hours. It made no sense. But Szeth did not ask questions.

At the edge of the room, he passed rows of unwavering azure lights that bulged out where wall met ?oor. They held sapphires infused with Stormlight. Profane. How could the men of these lands use something so sacred for mere illumination? Worse, the Alethi scholars were said to be close to creating new Shardblades. Szeth hoped that was just wishful boasting. For if it did happen, the world would be changed. Likely in a way that ended with people in all countries—from distant Thaylenah to towering Jah Keved—speaking Alethi to their children.

They were a grand people, these Alethi. Even drunk, there was a natural nobility to them. Tall and well made, the men dressed in dark silk coats that buttoned down the sides of the chest and were elaborately embroidered in silver or gold. Each one looked a general on the ?eld.

The women were even more splendid. They wore grand silk dresses, tightly ?tted, the bright colors a contrast to the dark tones favored by the men. The left sleeve of each dress was longer than the right one, covering the hand. Alethi had an odd sense of propriety.

Their pure black hair was pinned up atop their heads, either in intricate weavings of braids or in loose piles. It was often woven with gold ribbons or ornaments, along with gems that glowed with Stormlight. Beautiful. Profane, but beautiful.

Szeth left the feasting chamber behind. Just outside, he passed the doorway into the Beggars’ Feast. It was an Alethi tradition, a room where some of the poorest men and women in the city were given a feast complementing that of the king and his guests. A man with a long grey and black beard slumped in the doorway, smiling foolishly—though whether from wine or a weak mind, Szeth could not tell.

“Have you seen me?” the man asked with slurred speech. He laughed, then began to speak in gibberish, reaching for a wineskin. So it was drink after all. Szeth brushed by, continuing past a line of statues depicting the Ten Heralds from ancient Vorin theology. Jezerezeh, Ishi, Kelek, Talenelat. He counted o? each one, and realized there were only nine here. One was conspicuously missing. Why had Shalash’s statue been removed? King Gavilar was said to be very devout in his Vorin worship. Too devout, by some people’s standards.

The hallway here curved to the right, running around the perimeter of the domed palace. They were on the king’s ?oor, two levels up, surrounded by rock walls, ceiling, and ?oor. That was profane. Stone was not to be trod upon. But what was he to do? He was Truthless. He did as his masters demanded.

Today, that included wearing white. Loose white trousers tied at the waist with a rope, and over them a ?lmy shirt with long sleeves, open at the front. White clothing for a killer was a tradition among the Parshendi. Although Szeth had not asked, his masters had explained why.

White to be bold. White to not blend into the night. White to give warning.

For if you were going to assassinate a man, he was entitled to see you coming.

Szeth turned right, taking the hallway directly toward the king’s chambers. Torches burned on the walls, their light unsatisfying to him, a meal of thin broth after a long fast. Flamespren danced around them, like large insects made solely of congealed light. The torches were useless to him. He reached for his pouch and the spheres it contained, but then hesitated when he saw more of the blue lights ahead: a pair of Stormlight lamps hanging on the wall, brilliant sapphires glowing at their hearts. Szeth walked up to one of these, holding out his hand to cup it around the glass-shrouded gemstone.

“You there!” a voice called in Alethi. There were two guards at the intersection. Double guard, for there were savages abroad in Kholinar this night. True, those savages were supposed to be allies now. But alliances could be shallow things indeed.

This one wouldn’t last the hour.

Szeth looked as the two guards approached. They carried spears; they weren’t lighteyes, and were therefore forbidden the sword. Their painted blue breastplates were ornate, however, as were their helms. They might be darkeyed, but they were high-ranking citizens with honored positions in the royal guard.

Stopping a few feet away, the guard at the front gestured with his spear. “Go on, now. This is no place for you.” He had tan Alethi skin and a thin mustache that ran all the way around his mouth, becoming a beard at the bottom.

Szeth didn’t move.

“Well?” the guard said. “What are you waiting for?”

Szeth breathed in deeply, drawing forth the Stormlight. It streamed into him, siphoned from the twin sapphire lamps on the walls, sucked in as if by his deep inhalation. The Stormlight raged inside of him, and the hallway suddenly grew darker, falling into shade like a hilltop cut o? from the sun by a transient cloud.

Szeth could feel the Light’s warmth, its fury, like a tempest that had been injected directly into his veins. The power of it was invigorating but dangerous. It pushed him to act. To move. To strike.

Holding his breath, he clung to the Stormlight. He could still feel it leaking out. Stormlight could be held for only a short time, a few minutes at most. It leaked away, the human body too porous a container. He had heard that the Voidbringers could hold it in perfectly. But, then, did they even exist? His punishment declared that they didn’t. His honor demanded that they did.

A?re with holy energy, Szeth turned to the guards. They could see that he was leaking Stormlight, wisps of it curling from his skin like luminescent smoke. The lead guard squinted, frowning. Szeth was sure the man had never seen anything like it before. As far as he knew, Szeth had killed every stonewalker who had ever seen what he could do.

“What . . . what are you?” The guard’s voice had lost its certainty. “Spirit or man?”

“What am I?” Szeth whispered, a bit of Light leaking from his lips as he looked past the man down the long hallway. “I’m . . . sorry.”

Szeth blinked, Lashing himself to that distant point down the hallway. Stormlight raged from him in a ?ash, chilling his skin, and the ground immediately stopped pulling him downward. Instead, he was pulled toward that distant point—it was as if, to him, that direction had suddenly become down.

This was a Basic Lashing, ?rst of his three kinds of Lashings. It gave him the ability to manipulate whatever force, spren, or god it was that held men to the ground. With this Lashing, he could bind people or objects to di?erent surfaces or in di?erent directions.

From Szeth’s perspective, the hallway was now a deep shaft down which he was falling, and the two guards stood on one of the sides. They were shocked when Szeth’s feet hit them, one for each face, throwing them over. Szeth shifted his view and Lashed himself to the ?oor. Light leaked from him. The ?oor of the hallway again became down, and he landed between the two guards, clothes crackling and dropping ?akes of frost. He rose, beginning the process of summoning his Shardblade.

One of the guards fumbled for his spear. Szeth reached down, touching the soldier’s shoulder while looking up. He focused on a point above him while willing the Light out of his body and into the guard, Lashing the poor man to the ceiling.

The guard yelped in shock as up became down for him. Light trailing from his form, he crashed into the ceiling and dropped his spear. It was not Lashed directly, and clattered back down to the ?oor near Szeth.

To kill. It was the greatest of sins. And yet here Szeth stood, Truthless, profanely walking on stones used for building. And it would not end. As Truthless, there was only one life he was forbidden to take.

And that was his own.

At the tenth beat of his heart, his Shardblade dropped into his waiting hand. It formed as if condensing from mist, water beading along the metal length. His Shardblade was long and thin, edged on both sides, smaller than most others. Szeth swept it out, carving a line in the stone ?oor and passing through the second guard’s neck.

As always, the Shardblade killed oddly; though it cut easily through stone, steel, or anything inanimate, the metal fuzzed when it touched living skin. It traveled through the guard’s neck without leaving a mark, but once it did, the man’s eyes smoked and burned. They blackened, shriveling up in his head, and he slumped forward, dead. A Shardblade did not cut living ?esh; it severed the soul itself.

Above, the ?rst guard gasped. He’d managed to get to his feet, even though they were planted on the ceiling of the hallway. “Shardbearer!” he shouted. “A Shardbearer assaults the king’s hall! To arms!”

Finally, Szeth thought. Szeth’s use of Stormlight was unfamiliar to the guards, but they knew a Shardblade when they saw one.

Szeth bent down and picked up the spear that had fallen from above. As he did so, he released the breath he’d been holding since drawing in the Stormlight. It sustained him while he held it, but those two lanterns hadn’t contained much of it, so he would need to breathe again soon. The Light began to leak away more quickly, now that he wasn’t holding his breath.

Szeth set the spear’s butt against the stone ?oor, then looked upward. The guard above stopped shouting, eyes opening wide as the tails of his shirt began to slip downward, the earth below reasserting its dominance. The Light steaming o? his body dwindled.

He looked down at Szeth. Down at the spear tip pointing directly at his heart. Violet fearspren crawled out of the stone ceiling around him.

The Light ran out. The guard fell.

He screamed as he hit, the spear impaling him through the chest. Szeth let the spear fall away, carried to the ground with a mu?ed thump by the body twitching on its end. Shardblade in hand, he turned down a side corridor, following the map he’d memorized. He ducked around a corner and ?attened himself against the wall just as a troop of guards reached the dead men. The newcomers began shouting immediately, continuing the alarm.

His instructions were clear. Kill the king, but be seen doing it. Let the Alethi know he was coming and what he was doing. Why? Why did the Parshendi agree to this treaty, only to send an assassin the very night of its signing?

More gemstones glowed on the walls of the hallway here. King Gavilar liked lavish display, and he couldn’t know that he was leaving sources of power for Szeth to use in his Lashings. The things Szeth did hadn’t been seen for millennia. Histories from those times were all but nonexistent, and the legends were horribly inaccurate.

Szeth peeked back out into the corridor. One of the guards at the inter section saw him, pointing and yelling. Szeth made sure they got a good look, then ducked away. He took a deep breath as he ran, drawing in Stormlight from the lanterns. His body came alive with it, and his speed increased, his muscles bursting with energy. Light became a storm inside of him; his blood thundered in his ears. It was terrible and wonderful at the same time.

Two corridors down, one to the side. He threw open the door of a storage room, then hesitated a moment—just long enough for a guard to round the corner and see him—before dashing into the room. Preparing for a Full Lashing, he raised his arm and commanded the Stormlight to pool there, causing the skin to burst alight with radiance. Then he ?ung his hand out toward the doorframe, spraying white luminescence across it like paint. He slammed the door just as the guards arrived.

The Stormlight held the door in the frame with the strength of a hundred arms. A Full Lashing bound objects together, holding them fast until the Stormlight ran out. It took longer to create—and drained Stormlight far more quickly—than a Basic Lashing. The door handle shook, and then the wood began to crack as the guards threw their weight against it, one man calling for an axe.

Szeth crossed the room in rapid strides, weaving around the shrouded furniture that had been stored here. It was of red cloth and deep expensive woods. He reached the far wall and—preparing himself for yet another blasphemy—he raised his Shardblade and slashed horizontally through the dark grey stone. The rock sliced easily; a Shardblade could cut any inanimate object. Two vertical slashes followed, then one across the bottom, cutting a large square block. He pressed his hand against it, willing Stormlight into the stone.

Behind him the room’s door began to crack. He looked over his shoulder and focused on the shaking door, Lashing the block in that direction. Frost crystallized on his clothing—Lashing something so large required a great deal of Stormlight. The tempest within him stilled, like a storm reduced to a drizzle.

He stepped aside. The large stone block shuddered, sliding into the room. Normally, moving the block would have been impossible. Its own weight would have held it against the stones below. Yet now, that same weight pulled it free; for the block, the direction of the room’s door was down. With a deep grinding sound, the block slid free of the wall and tumbled through the air, smashing furniture.

The soldiers ?nally broke through the door, staggering into the room just as the enormous block crashed into them.

Szeth turned his back on the terrible sound of the screams, the splintering of wood, the breaking of bones. He ducked and stepped through his new hole, entering the hallway outside.

He walked slowly, drawing Stormlight from the lamps he passed, siphoning it to him and stoking anew the tempest within. As the lamps dimmed, the corridor darkened. A thick wooden door stood at the end, and as he approached, small fearspren—shaped like globs of purple goo—began to wriggle from the masonry, pointing toward the doorway. They were drawn by the terror being felt on the other side.

Szeth pushed the door open, entering the last corridor leading to the king’s chambers. Tall, red ceramic vases lined the pathway, and they were interspersed with nervous soldiers. They ?anked a long, narrow rug. It was red, like a river of blood.

The spearmen in front didn’t wait for him to get close. They broke into a trot, lifting their short throwing spears. Szeth slammed his hand to the side, pushing Stormlight into the doorframe, using the third and ?nal type of Lashing, a Reverse Lashing. This one worked di?erently from the other two. It did not make the doorframe emit Stormlight; indeed, it seemed to pull nearby light into it, giving it a strange penumbra.

The spearmen threw, and Szeth stood still, hand on the doorframe. A Reverse Lashing required his constant touch, but took comparatively little Stormlight. During one, anything that approached him—particularly lighter objects—was instead pulled toward the Lashing itself.

The spears veered in the air, splitting around him and slamming into the wooden frame. As he felt them hit, Szeth leaped into the air and Lashed himself to the right wall, his feet hitting the stone with a slap.

He immediately reoriented his perspective. To his eyes, he wasn’t standing on the wall, the soldiers were, the blood-red carpet streaming between them like a long tapestry. Szeth bolted down the hallway, striking with his Shardblade, shearing through the necks of two men who had thrown spears at him. Their eyes burned, and they collapsed.

The other guards in the hallway began to panic. Some tried to attack him, others yelled for more help, still others cringed away from him. The attackers had trouble—they were disoriented by the oddity of striking at someone who hung on the wall. Szeth cut down a few, then ?ipped into the air, tucking into a roll, and Lashed himself back to the ?oor.

He hit the ground in the midst of the soldiers. Completely surrounded, but holding a Shardblade.

According to legend, the Shardblades were ?rst carried by the Knights Radiant uncounted ages ago. Gifts of their god, granted to allow them to ?ght horrors of rock and ?ame, dozens of feet tall, foes whose eyes burned with hatred. The Voidbringers. When your foe had skin as hard as stone itself, steel was useless. Something supernal was required.

Szeth rose from his crouch, loose white clothes rippling, jaw clenched against his sins. He struck out, his weapon ?ashing with re?ected torchlight. Elegant, wide swings. Three of them, one after another. He could neither close his ears to the screams that followed nor avoid seeing the men fall. They dropped round him like toys knocked over by a child’s careless kick. If the Blade touched a man’s spine, he died, eyes burning. If it cut through the core of a limb, it killed that limb. One soldier stumbled away from Szeth, arm ?opping uselessly on his shoulder. He would never be able to feel it or use it again.

Szeth lowered his Shardblade, standing among the cinder-eyed corpses. Here, in Alethkar, men often spoke of the legends—of mankind’s hardwon victory over the Voidbringers. But when weapons created to ?ght nightmares were turned against common soldiers, the lives of men became cheap things indeed.

Szeth turned and continued on his way, slippered feet falling on the soft red rug. The Shardblade, as always, glistened silver and clean. When one killed with a Blade, there was no blood. That seemed like a sign. The Shardblade was just a tool; it could not be blamed for the murders.

The door at the end of the hallway burst open. Szeth froze as a small group of soldiers rushed out, ushering a man in regal robes, his head ducked as if to avoid arrows. The soldiers wore deep blue, the color of the King’s Guard, and the corpses didn’t make them stop and gawk. They were prepared for what a Shardbearer could do. They opened a side door and shoved their ward through, several leveling spears at Szeth as they backed out.

Another ?gure stepped from the king’s quarters; he wore glistening blue armor made of smoothly interlocking plates. Unlike common plate armor, however, this armor had no leather or mail visible at the joints— just smaller plates, ?tting together with intricate precision. The armor was beautiful, the blue inlaid with golden bands around the edges of each piece of plate, the helm ornamented with three waves of small, hornlike wings.

Shardplate, the customary complement to a Shardblade. The newcomer carried a sword as well, an enormous Shardblade six feet long with a design along the blade like burning ?ames, a weapon of silvery metal that gleamed and almost seemed to glow. A weapon designed to slay dark gods, a larger counterpart to the one Szeth carried.

Szeth hesitated. He didn’t recognize the armor; he had not been warned that he would be set at this task, and hadn’t been given proper time to memorize the various suits of Plate or Blades owned by the Alethi. But a Shardbearer would have to be dealt with before he chased the king; he could not leave such a foe behind.

Besides, perhaps a Shardbearer could defeat him, kill him and end his miserable life. His Lashings wouldn’t work directly on someone in Shardplate, and the armor would enhance the man, strengthen him. Szeth’s honor would not allow him to betray his mission or seek death. But if that death occurred, he would welcome it.

The Shardbearer struck, and Szeth Lashed himself to the side of the hallway, leaping with a twist and landing on the wall. He danced backward, Blade held at the ready. The Shardbearer fell into an aggressive posture, using one of the swordplay stances favored here in the East. He moved far more nimbly than one would expect for a man in such bulky armor. Shardplate was special, as ancient and magical as the Blades it complemented.

The Shardbearer struck. Szeth skipped to the side and Lashed himself to the ceiling as the Shardbearer’s Blade sliced into the wall. Feeling a thrill at the contest, Szeth dashed forward and attacked downward with an overhand blow, trying to hit the Shardbearer’s helm. The man ducked, going down on one knee, letting Szeth’s Blade cleave empty air.

Szeth leaped backward as the Shardbearer swung upward with his Blade, slicing into the ceiling. Szeth didn’t own a set of Plate himself, and didn’t care to. His Lashings interfered with the gemstones that powered

Shardplate, and he had to choose one or the other.

As the Shardbearer turned, Szeth sprinted forward across the ceiling. As expected, the Shardbearer swung again, and Szeth leaped to the side, rolling. He came up from his roll and ?ipped, Lashing himself to the ?oor again. He spun to land on the ground behind the Shardbearer. He slammed his Blade into his opponent’s open back.

Unfortunately, there was one major advantage Plate o?ered: It could block a Shardblade. Szeth’s weapon hit solidly, causing a web of glowing lines to spread out across the back of the armor, and Stormlight began to leak free from them. Shardplate didn’t dent or bend like common metal. Szeth would have to hit the Shardbearer in the same location at least once more to break through.

Szeth danced out of range as the Shardbearer swung in anger, trying to cut at Szeth’s knees. The tempest within Szeth gave him many advantages— including the ability to quickly recover from small wounds. But it would not restore limbs killed by a Shardblade.

He rounded the Shardbearer, then picked a moment and dashed forward. The Shardbearer swung again, but Szeth brie?y Lashed himself to the ceiling for lift. He shot into the air, cresting over the swing, then immediately Lashed himself back to the ?oor. He struck as he landed, but the Shardbearer recovered quickly and executed a perfect follow-through stroke, coming within a ?nger of hitting Szeth.

The man was dangerously skilled with that Blade. Many Shardbearers depended too much on the power of their weapon and armor. This man was di?erent.

Szeth jumped to the wall and struck at the Shardbearer with quick, terse attacks, like a snapping eel. The Shardbearer fended him o? with wide, sweeping counters. His Blade’s length kept Szeth at bay.

This is taking too long! Szeth thought. If the king slipped away into hiding, Szeth would fail in his mission no matter how many people he killed. He ducked in for another strike, but the Shardbearer forced him back. Each second this ?ght lasted was another for the king’s escape.

It was time to be reckless. Szeth launched into the air, Lashing himself to the other end of the hallway and falling feet-?rst toward his adversary. The Shardbearer didn’t hesitate to swing, but Szeth Lashed himself down at an angle, dropping immediately. The Shardblade swished through the air above him.

He landed in a crouch, using his momentum to throw himself forward, and swung at the Shardbearer’s side, where the Plate had cracked. He hit with a powerful blow. That piece of the Plate shattered, bits of molten metal streaking away. The Shardbearer grunted, dropping to one knee, raising a hand to his side. Szeth raised a foot to the man’s side and shoved him backward with a Stormlight-enhanced kick.

The heavy Shardbearer crashed into the door of the king’s quarters, smashing it and falling partway into the room beyond. Szeth left him, ducking instead through the doorway to the right, following the way the king had gone. The hallway here had the same red carpet, and Stormlight lamps on the walls gave Szeth a chance to recharge the tempest within.

Energy blazed within him again, and he sped up. If he could get far enough ahead, he could deal with the king, then turn back to ?ght o? the Shardbearer. It wouldn’t be easy. A Full Lashing on a doorway wouldn’t stop a Shardbearer, and that Plate would let the man run supernaturally fast. Szeth glanced over his shoulder.

The Shardbearer wasn’t following. The man sat up in his armor, looking dazed. Szeth could just barely see him, sitting in the doorway, surrounded by broken bits of wood. Perhaps Szeth had wounded him more than he’d thought.

Or maybe . . .

Szeth froze. He thought of the ducked head of the man who’d been rushed out, face obscured. The Shardbearer still wasn’t following. He was so skilled. It was said that few men could rival Gavilar Kholin’s swordsmanship. Could it be?

Szeth turned and dashed back, trusting his instincts. As soon as the Shardbearer saw him, he climbed to his feet with alacrity. Szeth ran faster. What was the safest place for your king? In the hands of some guards,

?eeing? Or protected in a suit of Shardplate, left behind, dismissed as a bodyguard?

Clever, Szeth thought as the formerly sluggish Shardbearer fell into another battle stance. Szeth attacked with renewed vigor, swinging his Blade in a ?urry of strikes. The Shardbearer—the king—aggressively struck out with broad, sweeping blows. Szeth pulled away from one of these, feeling the wind of the weapon passing just inches before him. He timed his next move, then dashed forward, ducking underneath the king’s follow-through.

The king, expecting another strike at his side, twisted with his arm held protectively to block the hole in his Plate. That gave Szeth the room to run past him and into the king’s chambers.

The king spun around to follow, but Szeth ran through the lavishly furnished chamber, ?inging out his hand, touching pieces of furniture he passed. He infused them with Stormlight, Lashing them to a point behind the king. The furniture tumbled as if the room had been turned on its side, couches, chairs, and tables dropping toward the surprised king. Gavilar made the mistake of chopping at them with his Shardblade. The weapon easily sheared through a large couch, but the pieces still crashed into him, making him stumble. A footstool hit him next, throwing him to the ground.

Gavilar rolled out of the way of the furniture and charged forward, Plate leaking streams of Light from the cracked sections. Szeth gathered himself, then leaped into the air, Lashing himself backward and to the right as the king arrived. He zipped out of the way of the king’s blow, then Lashed himself forward with two Basic Lashings in a row. Stormlight ?ashed out of him, clothing freezing, as he was pulled toward the king at twice the speed of a normal fall.

The king’s posture indicated surprise as Szeth lurched in midair, then spun toward him, swinging. He slammed his Blade into the king’s helm, then immediately Lashed himself to the ceiling and fell upward, slamming into the stone roof above. He’d Lashed himself in too many directions too quickly, and his body had lost track, making it di?cult to land gracefully. He stumbled back to his feet.

Below, the king stepped back, trying to get into position to swing up at Szeth. The man’s helm was cracked, leaking Stormlight, and he stood protectively, defending the side with the broken plate. The king used a onehanded swing, reaching for the ceiling. Szeth immediately Lashed himself downward, judging that the king’s attack would leave him unable to get his sword back in time.

Szeth underestimated his opponent. The king stepped into Szeth’s attack, trusting his helm to absorb the blow. Just as Szeth hit the helm a second time—shattering it—Gavilar punched with his o? hand, slamming his gauntleted ?st into Szeth’s face.

Blinding light ?ashed in Szeth’s eyes, a counterpoint to the sudden agony that crashed across his face. Everything blurred, his vision fading.

Pain. So much pain!

He screamed, Stormlight leaving him in a rush, and he slammed back into something hard. The balcony doors. More pain broke out across his shoulders, as if someone had stabbed him with a hundred daggers, and he hit the ground and rolled to a stop, muscles trembling. The blow would have killed an ordinary man.

No time for pain. No time for pain. No time for pain!

He blinked, shaking his head, the world blurry and dark. Was he blind? No. It was dark outside. He was on the wooden balcony; the force of the blow had thrown him through the doors. Something was thumping. Heavy footfalls. The Shardbearer!

Szeth stumbled to his feet, vision swimming. Blood streamed from the side of his face, and Stormlight rose from his skin, blinding his left eye. The Light. It would heal him, if it could. His jaw felt unhinged. Broken? He’d dropped his Shardblade.

A lumbering shadow moved in front of him; the Shardbearer’s armor had leaked enough Stormlight that the king was having trouble walking. But he was coming.

Szeth screamed, kneeling, infusing Stormlight into the wooden balcony, Lashing it downward. The air frosted around him. The tempest roared, traveling down his arms into the wood. He Lashed it downward, then did it again. He Lashed a fourth time as Gavilar stepped onto the balcony. It lurched under the extra weight. The wood cracked, straining.

The Shardbearer hesitated.

Szeth Lashed the balcony downward a ?fth time. The balcony supports shattered and the entire structure broke free from the building. Szeth screamed through a broken jaw and used his ?nal bit of Stormlight to Lash himself to the side of the building. He fell to the side, passing the shocked Shardbearer, then hit the wall and rolled.

The balcony dropped away, the king looking up with shock as he lost his footing. The fall was brief. In the moonlight, Szeth watched solemnly— vision still fuzzy, blinded in one eye—as the structure crashed to the stone ground below. The wall of the palace trembled, and the crash of broken wood echoed from the nearby buildings.

Still lying on the side of the wall, Szeth groaned, climbing to his feet. He felt weak; he’d used up his Stormlight too quickly, straining his body. He stumbled down the side of the building, approaching the wreckage, barely able to remain standing.

The king was still moving. Shardplate would protect a man from such a fall, but a large length of bloodied wood stuck up through Gavilar’s side, piercing him where Szeth had broken the Plate earlier. Szeth knelt down, inspecting the man’s pain-wracked face. Strong features, square chin, black beard ?ecked with white, striking pale green eyes. Gavilar Kholin.

“I . . . expected you . . . to come,” the king said between gasps.

Szeth reached underneath the front of the man’s breastplate, tapping the straps there. They unfastened, and he pulled the front of the breastplate free, exposing the gemstones on its interior. Two had been cracked and burned out. Three still glowed. Numb, Szeth breathed in sharply, absorbing the Light.

The storm began to rage again. More Light rose from the side of his face, repairing his damaged skin and bones. The pain was still great; Stormlight healing was far from instantaneous. It would be hours before he recovered.

The king coughed. “You can tell . . . Thaidakar . . . that he’s too late. . . .”

“I don’t know who that is,” Szeth said, standing, his words slurring from his broken jaw. He held his hand to the side, resummoning his Shardblade.

The king frowned. “Then who . . . ? Restares? Sadeas? I never thought . . .”

“My masters are the Parshendi,” Szeth said. Ten heartbeats passed, and his Blade dropped into his hand, wet with condensation.

“The Parshendi? That makes no sense.” Gavilar coughed, hand quivering, reaching toward his chest and fumbling at a pocket. He pulled out a small crystalline sphere tied to a chain. “You must take this. They must not get it.” He seemed dazed. “Tell . . . tell my brother . . . he must ?nd the most important words a man can say. . . .”

Gavilar fell still.

Szeth hesitated, then knelt down and took the sphere. It was odd, unlike any he’d seen before. Though it was completely dark, it seemed to glow somehow. With a light that was black.

The Parshendi? Gavilar had said. That makes no sense.

“Nothing makes sense anymore,” Szeth whispered, tucking the strange sphere away. “It’s all unraveling. I am sorry, King of the Alethi. I doubt that you care. Not anymore, at least.” He stood up. “At least you won’t have to watch the world ending with the rest of us.”

Beside the king’s body, his Shardblade materialized from mist, clattering to the stones now that its master was dead. It was worth a fortune; kingdoms had fallen as men vied to possess a single Shardblade.

Shouts of alarm came from inside the palace. Szeth needed to go. But . . .

Tell my brother . . .

To Szeth’s people, a dying request was sacred. He took the king’s hand, dipping it in the man’s own blood, then used it to scrawl on the wood, Brother. You must ?nd the most important words a man can say.

With that, Szeth escaped into the night. He left the king’s Shardblade; he had no use for it. The Blade Szeth already carried was curse enough.

Part One: Above Silence

“You’ve killed me. Bastards, you’ve killed me! While the sun is still hot, I die!”

—Collected on the fifth day of the week Chach of the month Betab of the year 1171, ten seconds before death. Subject was a darkeyed soldier thirty-one years of age. Sample is considered questionable.

FIVE YEARS LATER

I’m going to die, aren’t I?” Cenn asked.

The weathered veteran beside Cenn turned and inspected him. The veteran wore a full beard, cut short. At the sides, the black hairs were starting to give way to grey.

I’m going to die, Cenn thought, clutching his spear—the shaft slick with sweat. I’m going to die. Oh, Stormfather. I’m going to die. . . .

“How old are you, son?” the veteran asked. Cenn didn’t remember the man’s name. It was hard to recall anything while watching that other army form lines across the rocky battle?eld. That lining up seemed so civil. Neat, organized. Shortspears in the front ranks, longspears and javelins next, archers at the sides. The darkeyed spearmen wore equipment like Cenn’s: leather jerkin and knee-length skirt with a simple steel cap and a matching breastplate.

Many of the lighteyes had full suits of armor. They sat astride horses, their honor guards clustering around them with breastplates that gleamed burgundy and deep forest green. Were there Shardbearers among them? Brightlord Amaram wasn’t a Shardbearer. Were any of his men? What if Cenn had to ?ght one? Ordinary men didn’t kill Shardbearers. It had happened so infrequently that each occurrence was now legendary.

It’s really happening, he thought with mounting terror. This wasn’t a drill in the camp. This wasn’t training out in the ?elds, swinging sticks. This was real. Facing that fact—his heart pounding like a frightened animal in his chest, his legs unsteady—Cenn suddenly realized that he was a coward. He shouldn’t have left the herds! He should never have—

“Son?” the veteran said, voice ?rm. “How old are you?”

“Fifteen, sir.”

“And what’s your name?”

“Cenn, sir.”

The mountainous, bearded man nodded. “I’m Dallet.”

“Dallet,” Cenn repeated, still staring out at the other army. There were so many of them! Thousands. “I’m going to die, aren’t I?”

“No.” Dallet had a gru? voice, but somehow that was comforting. “You’re going to be just ?ne. Keep your head on straight. Stay with the squad.”

“But I’ve barely had three months’ training!” He swore he could hear faint clangs from the enemy’s armor or shields. “I can barely hold this spear! Stormfather, I’m dead. I can’t—”

“Son,” Dallet interrupted, soft but ?rm. He raised a hand and placed it on Cenn’s shoulder. The rim of Dallet’s large round shield re?ected the light from where it hung on his back. “You are going to be ?ne.”

“How can you know?” It came out as a plea.

“Because, lad. You’re in Kaladin Stormblessed’s squad.” The other soldiers nearby nodded in agreement.

Behind them, waves and waves of soldiers were lining up—thousands of them. Cenn was right at the front, with Kaladin’s squad of about thirty other men. Why had Cenn been moved to a new squad at the last moment? It had something to do with camp politics.

Why was this squad at the very front, where casualties were bound to be the greatest? Small fearspren—like globs of purplish goo—began to climb up out of the ground and gather around his feet. In a moment of sheer panic, he nearly dropped his spear and scrambled away. Dallet’s hand tightened on his shoulder. Looking up into Dallet’s con?dent black eyes, Cenn hesitated.

“Did you piss before we formed ranks?” Dallet asked. “I didn’t have time to—”

“Go now.”

“Here? ”

“If you don’t, you’ll end up with it running down your leg in battle, distracting you, maybe killing you. Do it.”

Embarrassed, Cenn handed Dallet his spear and relieved himself onto the stones. When he ?nished, he shot glances at those next to him. None of Kaladin’s soldiers smirked. They stood steady, spears to their sides, shields on their backs.

The enemy army was almost ?nished. The ?eld between the two forces was bare, ?at slickrock, remarkably even and smooth, broken only by occasional rockbuds. It would have made a good pasture. The warm wind blew in Cenn’s face, thick with the watery scents of last night’s highstorm.

“Dallet!” a voice said.

A man walked up through the ranks, carrying a shortspear that had two leather knife sheaths strapped to the haft. The newcomer was a young man—perhaps four years older than Cenn’s ?fteen—but he was taller by several ?ngers than even Dallet. He wore the common leathers of a spearman, but under them was a pair of dark trousers. That wasn’t supposed to be allowed.

His black Alethi hair was shoulder-length and wavy, his eyes a dark brown. He also had knots of white cord on the shoulders of his jerkin, marking him as a squadleader.

The thirty men around Cenn snapped to attention, raising their spears in salute. This is Kaladin Stormblessed? Cenn thought incredulously. This youth?

“Dallet, we’re soon going to have a new recruit,” Kaladin said. He had a strong voice. “I need you to . . .” He trailed o? as he noticed Cenn.

“He found his way here just a few minutes ago, sir,” Dallet said with a smile. “I’ve been gettin’ him ready.”

“Well done,” Kaladin said. “I paid good money to get that boy away from Gare. That man’s so incompetent he might as well be ?ghting for the other side.”

What? Cenn thought. Why would anyone pay to get me?

“What do you think about the ?eld?” Kaladin asked. Several of the other spearmen nearby raised hands to shade from the sun, scanning the rocks.

“That dip next to the two boulders on the far right?” Dallet asked.

Kaladin shook his head. “Footing’s too rough.”

“Aye. Perhaps it is. What about the short hill over there? Far enough to avoid the ?rst fall, close enough to not get too far ahead.”

Kaladin nodded, though Cenn couldn’t see what they were looking at. “Looks good.”

“The rest of you louts hear that?” Dallet shouted. The men raised their spears high.

“Keep an eye on the new boy, Dallet,” Kaladin said. “He won’t know the signs.”

“Of course,” Dallet said, smiling. Smiling! How could the man smile? The enemy army was blowing horns. Did that mean they were ready? Even though Cenn had just relieved himself, he felt a trickle of urine run down his leg.

“Stay ?rm,” Kaladin said, then trotted down the front line to talk to the next squadleader over. Behind Cenn and the others, the dozens of ranks were still growing. The archers on the sides prepared to ?re.

“Don’t worry, son,” Dallet said. “We’ll be ?ne. Squadleader Kaladin is lucky.”

The soldier on the other side of Cenn nodded. He was a lanky, redhaired Veden, with darker tan skin than the Alethi. Why was he ?ghting in an Alethi army? “That’s right. Kaladin, he’s stormblessed, right sure he is. We only lost . . . what, one man last battle?”

“But someone did die,” Cenn said.

Dallet shrugged. “People always die. Our squad loses the fewest. You’ll see.”

Kaladin ?nished conferring with the other squadleader, then jogged back to his team. Though he carried a shortspear—meant to be wielded one-handed with a shield in the other hand—his was a hand longer than those held by the other men.

“At the ready, men!” Dallet called. Unlike the other squadleaders, Kaladin didn’t fall into rank, but stood out in front of his squad.

The men around Cenn shu?ed, excited. The sounds were repeated through the vast army, the stillness giving way before eagerness. Hundreds of feet shu?ing, shields slapping, clasps clanking. Kaladin remained motionless, staring down the other army. “Steady, men,” he said without turning.

Behind, a lighteyed o?cer passed on horseback. “Be ready to ?ght! I want their blood, men. Fight and kill!”

“Steady,” Kaladin said again, after the man passed.

“Be ready to run,” Dallet said to Cenn.

“Run? But we’ve been trained to march in formation! To stay in our line!”

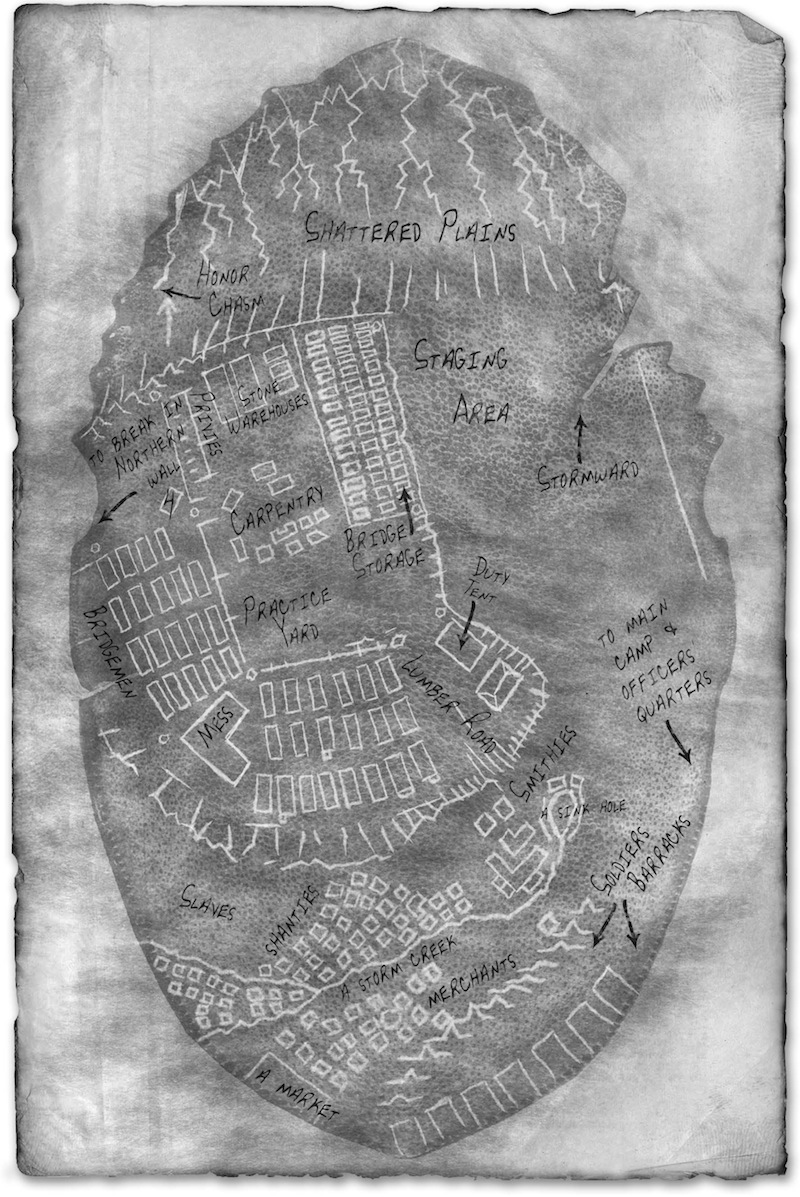

“Sure,” Dallet said. “But most of the men don’t have much more training than you. Those who can ?ght well end up getting sent to the Shattered Plains to battle the Parshendi. Kaladin’s trying to get us into shape to go there, to ?ght for the king.” Dallet nodded down the line. “Most of these here will break and charge; the lighteyes aren’t good enough commanders to keep them in formation. So stay with us and run.”

“Should I have my shield out?” Around Kaladin’s team, the other ranks were unhooking their shields. But Kaladin’s squad left their shields on their backs.

Before Dallet could answer, a horn blew from behind.

“Go!” Dallet said.

Cenn didn’t have much choice. The entire army started moving in a clamor of marching boots. As Dallet had predicted, the steady march didn’t last long. Some men began yelling, the roar taken up by others. Lighteyes called for them to go, run, ?ght. The line disintegrated.

As soon as that happened, Kaladin’s squad broke into a dash, running out into the front at full speed. Cenn scrambled to keep up, panicked and terri?ed. The ground wasn’t as smooth as it had seemed, and he nearly tripped on a hidden rockbud, vines withdrawn into its shell.

He righted himself and kept going, holding his spear in one hand, his shield clapping against his back. The distant army was in motion as well, their soldiers charging down the ?eld. There was no semblance of a battle formation or a careful line. This wasn’t anything like the training had claimed it would be.

Cenn didn’t even know who the enemy was. A landlord was encroaching on Brightlord Amaram’s territory—the land owned, ultimately, by Highprince Sadeas. It was a border skirmish, and Cenn thought it was with another Alethi princedom. Why were they ?ghting each other? Perhaps the king would have put a stop to it, but he was on the Shattered Plains, seeking vengeance for the murder of King Gavilar ?ve years before.

The enemy had a lot of archers. Cenn’s panic climbed to a peak as the ?rst wave of arrows ?ew into the air. He stumbled again, itching to take out his shield. But Dallet grabbed his arm and yanked him forward.

Hundreds of arrows split the sky, dimming the sun. They arced and fell, dropping like skyeels upon their prey. Amaram’s soldiers raised shields. But not Kaladin’s squad. No shields for them.

Cenn screamed.

And the arrows slammed into the middle ranks of Amaram’s army, behind him. Cenn glanced over his shoulder, still running. The arrows fell behind him. Soldiers screamed, arrows broke against shields; only a few straggling arrows landed anywhere near the front ranks.

“Why?” he yelled at Dallet. “How did you know?”

“They want the arrows to hit where the men are most crowded,” the large man replied. “Where they’ll have the greatest chance of ?nding a body.”

Several other groups in the van left their shields lowered, but most ran awkwardly with their shields angled up to the sky, worried about arrows that wouldn’t hit them. That slowed them, and they risked getting trampled by the men behind who were getting hit. Cenn itched to raise his shield anyway; it felt so wrong to run without it.

The second volley hit, and men screamed in pain. Kaladin’s squad barreled toward the enemy soldiers, some of whom were dying to arrows from Amaram’s archers. Cenn could hear the enemy soldiers bellowing war cries,

could make out individual faces. Suddenly, Kaladin’s squad pulled to a halt, forming a tight group. They’d reached the small incline that Kaladin and Dallet had chosen earlier.

Dallet grabbed Cenn and shoved him to the very center of the formation. Kaladin’s men lowered spears, pulling out shields as the enemy bore down on them. The charging foe used no careful formation; they didn’t keep the ranks of longspears in back and shortspears in front. They all just ran forward, yelling in a frenzy.

Cenn scrambled to get his shield unlatched from his back. Clashing spears rang in the air as squads engaged one another. A group of enemy spearmen rushed up to Kaladin’s squad, perhaps coveting the higher ground. The three dozen attackers had some cohesion, though they weren’t in as tight a formation as Kaladin’s squad was.

The enemy seemed determined to make up for it in passion; they bellowed and screamed in fury, rushing Kaladin’s line. Kaladin’s team held rank, defending Cenn as if he were some lighteyes and they were his honor guard. The two forces met with a crash of metal on wood, shields slamming together. Cenn cringed back.

It was over in a few eyeblinks. The enemy squad pulled back, leaving two dead on the stone. Kaladin’s team hadn’t lost anyone. They held their bristling V formation, though one man stepped back and pulled out a bandage to wrap a thigh wound. The rest of the men closed in to ?ll the spot. The wounded man was hulking and thick-armed; he cursed, but the wound didn’t look bad. He was on his feet in a moment, but didn’t return to the place where he’d been. Instead, he moved down to one end of the V formation, a more protected spot.

The battle?eld was chaos. The two armies mingled indistinguishably; sounds of clanging, crunching, and screaming churned in the air. Many of the squads broke apart, members rushing from one encounter to another. They moved like hunters, groups of three or four seeking lone individuals, then brutally falling on them.

Kaladin’s team held its ground, engaging only enemy squads that got too close. Was this what a battle really was? Cenn’s practice had trained him for long ranks of men, shoulder to shoulder. Not this frenzied intermixing, this brutal pandemonium. Why didn’t more hold formation?

The real soldiers are all gone, Cenn thought. O? ?ghting in a real battle at the Shattered Plains. No wonder Kaladin wants to get his squad there.

Spears ?ashed on all sides; it was di?cult to tell friend from foe, despite the emblems on breastplates and colored paint on shields. The battle?eld broke down into hundreds of small groups, like a thousand di?erent wars happening at the same time.

After the ?rst few exchanges, Dallet took Cenn by the shoulder and placed him in the rank at the very bottom of the V pattern. Cenn, however, was worthless. When Kaladin’s team engaged enemy squads, all of his train ing ?ed him. It took everything he had to just remain there, holding his spear outward and trying to look threatening.

For the better part of an hour, Kaladin’s squad held their small hill, working as a team, shoulder to shoulder. Kaladin often left his position at the front, rushing this way and that, banging his spear on his shield in a strange rhythm.

Those are signals, Cenn realized as Kaladin’s squad moved from the V shape into a ring. With the screams of the dying and the thousands of men calling to others, it was nearly impossible to hear a single person’s voice. But the sharp clang of the spear against the metal plate on Kaladin’s shield was clear. Each time they changed formations, Dallet grabbed Cenn by the shoulder and steered him.

Kaladin’s team didn’t chase down stragglers. They remained on the defensive. And, while several of the men in Kaladin’s team took wounds, none of them fell. Their squad was too intimidating for the smaller groups, and larger enemy units retreated after a few exchanges, seeking easier foes.

Eventually something changed. Kaladin turned, watching the tides of the battle with discerning brown eyes. He raised his spear and smacked his shield in a quick rhythm he hadn’t used before. Dallet grabbed Cenn by the arm and pulled him away from the small hill. Why abandon it now?

Just then, the larger body of Amaram’s force broke, the men scattering. Cenn hadn’t realized how poorly the battle in this quarter had been going for his side. As Kaladin’s team retreated, they passed many wounded and dying, and Cenn grew nauseated. Soldiers were sliced open, their insides spilling out.

He didn’t have time for horror; the retreat quickly turned into a rout. Dallet cursed, and Kaladin beat his shield again. The squad changed direction, heading eastward. There, Cenn saw, a larger group of Amaram’s soldiers was holding.

But the enemy had seen the ranks break, and that made them bold. They rushed forward in clusters, like wild axehounds hunting stray hogs. Before Kaladin’s team was halfway across the ?eld of dead and dying, a large group of enemy soldiers intercepted them. Kaladin reluctantly banged his shield; his squad slowed.

Cenn felt his heart begin to thump faster and faster. Nearby, a squad of Amaram’s soldiers was consumed; men stumbled and fell, screaming, trying to get away. The enemies used their spears like skewers, killing men on the ground like cremlings.

Kaladin’s men met the enemy in a crash of spears and shields. Bodies shoved on all sides, and Cenn was spun about. In the jumble of friend and foe, dying and killing, Cenn grew overwhelmed. So many men running in so many directions!

He panicked, scrambling for safety. A group of soldiers nearby wore Alethi uniforms. Kaladin’s squad. Cenn ran for them, but when some turned toward him, Cenn was terri?ed to realize he didn’t recognize them. This wasn’t Kaladin’s squad, but a small group of unfamiliar soldiers holding an uneven, broken line. Wounded and terri?ed, they scattered as soon as an enemy squad got close.

Cenn froze, holding his spear in a sweaty hand. The enemy soldiers charged right for him. His instincts urged him to ?ee, yet he had seen so many men picked o? one at a time. He had to stand! He had to face them! He couldn’t run, he couldn’t—

He yelled, stabbing his spear at the lead soldier. The man casually knocked the weapon aside with his shield, then drove his shortspear into Cenn’s thigh. The pain was hot, so hot that the blood squirting out on his leg felt cold by comparison. Cenn gasped.

The soldier yanked the weapon free. Cenn stumbled backward, drop ping his spear and shield. He fell to the rocky ground, splashing in someone else’s blood. His foe raised a spear high, a looming silhouette against the stark blue sky, ready to ram it into Cenn’s heart.

And then he was there.

Squadleader. Stormblessed. Kaladin’s spear came as if out of nowhere, narrowly de?ecting the blow that was to have killed Cenn. Kaladin set himself in front of Cenn, alone, facing down six spearmen. He didn’t ?inch. He charged.

It happened so quickly. Kaladin swept the feet from beneath the man who had stabbed Cenn. Even as that man fell, Kaladin reached up and ?ipped a knife from one of the sheaths tied about his spear. His hand snapped, knife ?ashing and hitting the thigh of a second foe. That man fell to one knee, screaming.

A third man froze, looking at his fallen allies. Kaladin shoved past a wounded enemy and slammed his spear into the gut of the third man. A fourth man fell with a knife to the eye. When had Kaladin grabbed that knife? He spun between the last two, his spear a blur, wielding it like a quartersta?. For a moment, Cenn thought he could see something surrounding the squadleader. A warping of the air, like the wind itself become visible.

I’ve lost a lot of blood. It’s ?owing out so quickly. . . .

Kaladin spun, knocking aside attacks, and the last two spearmen fell with gurgles that Cenn thought sounded surprised. Foes all down, Kaladin turned and knelt beside Cenn. The squadleader set aside his spear and whipped a white strip of cloth from his pocket, then e?ciently wrapped it tight around Cenn’s leg. Kaladin worked with the ease of one who had bound wounds dozens of times before.

“Kaladin, sir!” Cenn said, pointing at one of the soldiers Kaladin had wounded. The enemy man held his leg as he stumbled to his feet. In a second, however, mountainous Dallet was there, shoving the foe with his shield. Dallet didn’t kill the wounded man, but let him stumble away, unarmed.

The rest of the squad arrived and formed a ring around Kaladin, Dallet, and Cenn. Kaladin stood up, raising his spear to his shoulder; Dallet handed him back his knives, retrieved from the fallen foes.

“Had me worried there, sir,” Dallet said. “Running o? like that.”

“I knew you’d follow,” Kaladin said. “Raise the red banner. Cyn, Korater, you’re going back with the boy. Dallet, hold here. Amaram’s line is bulging in this direction. We should be safe soon.”

“And you, sir?” Dallet asked.

Kaladin looked across the ?eld. A pocket had opened in the enemy forces, and a man rode there on a white horse, swinging about him with a wicked mace. He wore full plate armor, polished and gleaming silver.

“A Shardbearer,” Cenn said.

Dallet snorted. “No, thank the Stormfather. Just a lighteyed o?cer. Shardbearers are far too valuable to waste on a minor border dispute.”

Kaladin watched the lighteyes with a seething hatred. It was the same hatred Cenn’s father had shown when he’d spoken of chull rustlers, or the hatred Cenn’s mother would display when someone mentioned Kusiri, who had run o? with the cobbler’s son.

“Sir?” Dallet said hesitantly.

“Subsquads Two and Three, pincer pattern,” Kaladin said, his voice hard. “We’re taking a brightlord o? his throne.”

“You sure that’s wise, sir? We’ve got wounded.”

Kaladin turned toward Dallet. “That’s one of Hallaw’s o?cers. He might be the one.”

“You don’t know that, sir.”

“Regardless, he’s a battalionlord. If we kill an o?cer that high, we’re all but guaranteed to be in the next group sent to the Shattered Plains. We’re taking him.” His eyes grew distant. “Imagine it, Dallet. Real soldiers. A warcamp with discipline and lighteyes with integrity. A place where our ?ghting will mean something.”

Dallet sighed, but nodded. Kaladin waved to a group of his soldiers; then they raced across the ?eld. A smaller group of soldiers, including Dallet, waited behind with the wounded. One of those—a thin man with black Alethi hair speckled with a handful of blond hairs, marking some foreign blood—pulled a long red ribbon from his pocket and attached it to his spear. He held the spear aloft, letting the ribbon ?ap in the wind.

“It’s a call for runners to carry our wounded o? the ?eld,” Dallet said to Cenn. “We’ll have you out of here soon. You were brave, standing against those six.”

“Fleeing seemed stupid,” Cenn said, trying to take his mind o? his throbbing leg. “With so many wounded on the ?eld, how can we think that the runners’ll come for us?”

“Squadleader Kaladin bribes them,” Dallet said. “They usually only carry o? lighteyes, but there are more runners than there are wounded lighteyes. The squadleader puts most of his pay into the bribes.”

“This squad is di?erent,” Cenn said, feeling light-headed. “Told you.”

“Not because of luck. Because of training.”

“That’s part of it. Part of it is because we know if we get hurt, Kaladin will get us o? the battle?eld.” He paused, looking over his shoulder. As Kaladin had predicted, Amaram’s line was surging back, recovering.

The mounted enemy lighteyes from before was energetically laying about with his mace. A group of his honor guard moved to one side, engaging Kaladin’s subsquads. The lighteyes turned his horse. He wore an open-fronted helm that had sloping sides and a large set of plumes on the top. Cenn couldn’t make out his eye color, but he knew it would be blue or green, maybe yellow or light grey. He was a brightlord, chosen at birth by the Heralds, marked for rule.

He impassively regarded those who fought nearby. Then one of Kaladin’s knives took him in the right eye.

The brightlord screamed, falling back o? the saddle as Kaladin somehow slipped through the lines and leaped upon him, spear raised.

“Aye, it’s part training,” Dallet said, shaking his head. “But it’s mostly him. He ?ghts like a storm, that one, and thinks twice as fast as other men. The way he moves sometimes . . .”

“He bound my leg,” Cenn said, realizing he was beginning to speak nonsense due to the blood loss. Why point out the bound leg? It was a simple thing.

Dallet just nodded. “He knows a lot about wounds. He can read glyphs too. He’s a strange man, for a lowly darkeyed spearman, our squadleader is.” He turned to Cenn. “But you should save your strength, son. The squadleader won’t be pleased if we lose you, not after what he paid to get you.”

“Why?” Cenn asked. The battle?eld was growing quieter, as if many of the dying men had already yelled themselves hoarse. Almost everyone around them was an ally, but Dallet still watched to make sure no enemy soldiers tried to strike at Kaladin’s wounded.

“Why, Dallet?” Cenn repeated, feeling urgent. “Why bring me into his squad? Why me?”

Dallet shook his head. “It’s just how he is. Hates the thought of young kids like you, barely trained, going to battle. Every now and again, he grabs one and brings him into his squad. A good half dozen of our men were once like you.” Dallet’s eyes got a far-o? look. “I think you all remind him of someone.”

Cenn glanced at his leg. Painspren—like small orange hands with overly long ?ngers—were crawling around him, reacting to his agony. They began turning away, scurrying in other directions, seeking other wounded. His pain was fading, his leg—his whole body—feeling numb.

He leaned back, staring up at the sky. He could hear faint thunder. That was odd. The sky was cloudless.

Dallet cursed.

Cenn turned, shocked out of his stupor. Galloping directly toward them was a massive black horse bearing a rider in gleaming armor that seemed to radiate light. That armor was seamless—no chain underneath, just smaller plates, incredibly intricate. The ?gure wore an unornamented full helm, and the plate was gilded. He carried a massive sword in one hand, fully as long as a man was tall. It wasn’t a simple, straight sword—it was curved, and the side that wasn’t sharp was ridged, like ?owing waves. Etchings covered its length.

It was beautiful. Like a work of art. Cenn had never seen a Shardbearer, but he knew immediately what this was. How could he ever have mistaken a simple armored lighteyes for one of these majestic creatures?

Hadn’t Dallet claimed there would be no Shardbearers on this battle ?eld? Dallet scrambled to his feet, calling for the subsquad to form up. Cenn just sat where he was. He couldn’t have stood, not with that leg wound.

He felt so light-headed. How much blood had he lost? He could barely think.

Either way, he couldn’t ?ght. You didn’t ?ght something like this. Sun gleamed against that plate armor. And that gorgeous, intricate, sinuous sword. It was like . . . like the Almighty himself had taken form to walk the battle?eld.

And why would you want to ?ght the Almighty?

Cenn closed his eyes.

“Ten orders. We were loved, once. Why have you forsaken us, Almighty! Shard of my soul, where have you gone?”

—Collected on the second day of Kakash, year 1171, five seconds before death. Subject was a lighteyed woman in her third decade.

EIGHT MONTHS LATER

Kaladin’s stomach growled as he reached through the bars and accepted the bowl of slop. He pulled the small bowl—more a cup— between the bars, sni?ed it, then grimaced as the caged wagon began to roll again. The sludgy grey slop was made from overcooked tallew grain, and this batch was ?ecked with crusted bits of yesterday’s meal.

Revolting though it was, it was all he would get. He began to eat, legs hanging out between the bars, watching the scenery pass. The other slaves in his cage clutched their bowls protectively, afraid that someone might steal from them. One of them tried to steal Kaladin’s food on the ?rst day. He’d nearly broken the man’s arm. Now everyone left him alone.

Suited him just ?ne.

He ate with his ?ngers, careless of the dirt. He’d stopped noticing dirt months ago. He hated that he felt some of that same paranoia that the others showed. How could he not, after eight months of beatings, deprivation, and brutality?

He fought down the paranoia. He wouldn’t become like them. Even if he’d given up everything else—even if all had been taken from him, even if there was no longer hope of escape. This one thing he would retain. He was a slave. But he didn’t need to think like one.

He ?nished the slop quickly. Nearby, one of the other slaves began to cough weakly. There were ten slaves in the wagon, all men, scraggly-bearded and dirty. It was one of three wagons in their caravan through the Unclaimed Hills.

The sun blazed reddish white on the horizon, like the hottest part of a smith’s ?re. It lit the framing clouds with a spray of color, paint thrown carelessly on a canvas. Covered in tall, monotonously green grass, the hills seemed endless. On a nearby mound, a small ?gure ?itted around the plants, dancing like a ?uttering insect. The ?gure was amorphous, vaguely translucent. Windspren were devious spirits who had a penchant for staying where they weren’t wanted. He’d hoped that this one had gotten bored and left, but as Kaladin tried to toss his wooden bowl aside, he found that it stuck to his ?ngers.

The windspren laughed, zipping by, nothing more than a ribbon of light without form. He cursed, tugging on the bowl. Windspren often played pranks like that. He pried at the bowl, and it eventually came free. Grumbling, he tossed it to one of the other slaves. The man quickly began to lick at the remnants of the slop.

“Hey,” a voice whispered.

Kaladin looked to the side. A slave with dark skin and matted hair was crawling up to him, timid, as if expecting Kaladin to be angry. “You’re not like the others.” The slave’s black eyes glanced upward, toward Kaladin’s forehead, which bore three brands. The ?rst two made a glyphpair, given to him eight months ago, on his last day in Amaram’s army. The third was fresh, given to him by his most recent master. Shash, the last glyph read. Dangerous.

The slave had his hand hidden behind his rags. A knife? No, that was ridiculous. None of these slaves could have hidden a weapon; the leaves hidden in Kaladin’s belt were as close as one could get. But old instincts could not be banished easily, so Kaladin watched that hand.

“I heard the guards talking,” the slave continued, shu?ing a little closer. He had a twitch that made him blink too frequently. “You’ve tried to escape before, they said. You have escaped before.”

Kaladin made no reply.

“Look,” the slave said, moving his hand out from behind his rags and revealing his bowl of slop. It was half full. “Take me with you next time,” he whispered. “I’ll give you this. Half my food from now until we get away. Please.” As he spoke, he attracted a few hungerspren. They looked like brown ?ies that ?itted around the man’s head, almost too small to see.

Kaladin turned away, looking out at the endless hills and their shifting, moving grasses. He rested one arm across the bars and placed his head against it, legs still hanging out.

“Well?” the slave asked.

“You’re an idiot. If you gave me half your food, you’d be too weak to escape if I were to ?ee. Which I won’t. It doesn’t work.”

“But—”

“Ten times,” Kaladin whispered. “Ten escape attempts in eight months, ?eeing from ?ve di?erent masters. And how many of them worked?”

“Well . . . I mean . . . you’re still here. . . .”

Eight months. Eight months as a slave, eight months of slop and beatings. It might as well have been an eternity. He barely remembered the army anymore. “You can’t hide as a slave,” Kaladin said. “Not with that brand on your forehead. Oh, I got away a few times. But they always found me. And then back I went.”

Once, men had called him lucky. Stormblessed. Those had been lies—if anything, Kaladin had bad luck. Soldiers were a superstitious sort, and though he’d initially resisted that way of thinking, it was growing harder and harder. Every person he had ever tried to protect had ended up dead. Time and time again. And now, here he was, in an even worse situation than where he’d begun. It was better not to resist. This was his lot, and he was resigned to it.

There was a certain power in that, a freedom. The freedom of not having to care.

The slave eventually realized Kaladin wasn’t going to say anything further, and so he retreated, eating his slop. The wagons continued to roll, ?elds of green extending in all directions. The area around the rattling wag ons was bare, however. When they approached, the grass pulled away, each individual stalk withdrawing into a pinprick hole in the stone. After the wagons moved on, the grass timidly poked back out and stretched its blades toward the air. And so, the cages moved along what appeared to be an open rock highway, cleared just for them.

This far into the Unclaimed Hills, the highstorms were incredibly powerful. The plants had learned to survive. That’s what you had to do, learn to survive. Brace yourself, weather the storm.

Kaladin caught a whi? of another sweaty, unwashed body and heard the sound of shu?ing feet. He looked suspiciously to the side, expecting that same slave to be back.

It was a di?erent man this time, though. He had a long black beard stuck with bits of food and snarled with dirt. Kaladin kept his own beard shorter, allowing Tvlakv’s mercenaries to hack it down periodically. Like Kaladin, the slave wore the remains of a brown sack tied with a rag, and he was darkeyed, of course—perhaps a deep dark green, though with dark eyes it was hard to tell. They all looked brown or black unless you caught them in the right light.

The newcomer cringed away, raising his hands. He had a rash on one hand, the skin just faintly discolored. He’d likely approached because he’d seen Kaladin respond to that other man. The slaves had been frightened of him since the ?rst day, but they were also obviously curious.

Kaladin sighed and turned away. The slave hesitantly sat down. “Mind if I ask how you became a slave, friend? Can’t help wondering. We’re all wondering.”

Judging by the accent and the dark hair, the man was Alethi, like Kaladin. Most of the slaves were. Kaladin didn’t reply to the question.

“Me, I stole a herd of chull,” the man said. He had a raspy voice, like sheets of paper rubbing together. “If I’d taken one chull, they might have just beaten me. But a whole herd. Seventeen head . . .” He chuckled to himself, admiring his own audacity.

In the far corner of the wagon, someone coughed again. They were a sorry lot, even for slaves. Weak, sickly, underfed. Some, like Kaladin, were repeat runaways—though Kaladin was the only one with a shash brand. They were the most worthless of a worthless caste, purchased at a steep discount. They were probably being taken for resale in a remote place where men were desperate for labor. There were plenty of small, independent cities along the coast of the Unclaimed Hills, places where Vorin rules governing the use of slaves were just a distant rumor.

Coming this way was dangerous. These lands were ruled by nobody, and by cutting across open land and staying away from established trade routes, Tvlakv could easily run afoul of unemployed mercenaries. Men who had no honor and no fear of slaughtering a slavemaster and his slaves in order to steal a few chulls and wagons.

Men who had no honor. Were there men who had honor?

No, Kaladin thought. Honor died eight months ago.

“So?” asked the scraggly-bearded man. “What did you do to get made a slave?”

Kaladin raised his arm against the bars again. “How did you get caught?”

“Odd thing, that,” the man said. Kaladin hadn’t answered his question, but he had replied. That seemed enough. “It was a woman, of course. Should have known she’d sell me.”

“Shouldn’t have stolen chulls. Too slow. Horses would have been better.”

The man laughed riotously. “Horses? What do you think me, a madman? If I’d been caught stealing those, I’d have been hanged. Chulls, at least, only earned me a slave’s brand.”

Kaladin glanced to the side. This man’s forehead brand was older than Kaladin’s, the skin around the scar faded to white. What was that glyph pair? “Sas morom,” Kaladin said. It was the highlord’s district where the man had originally been branded.

The man looked up with shock. “Hey! You know glyphs?” Several of the slaves nearby stirred at this oddity. “You must have an even better story than I thought, friend.”

Kaladin stared out over those grasses blowing in the mild breeze. Whenever the wind picked up, the more sensitive of the grass stalks shrank down into their burrows, leaving the landscape patchy, like the coat of a sickly horse. That windspren was still there, moving between patches of grass. How long had it been following him? At least a couple of months now. That was downright odd. Maybe it wasn’t the same one. They were impossible to tell apart.

“Well?” the man prodded. “Why are you here?”

“There are many reasons why I’m here,” Kaladin said. “Failures. Crimes. Betrayals. Probably the same for most every one of us.”

Around him, several of the men grunted in agreement; one of those grunts then degenerated into a hacking cough. Persistent coughing, a part of Kaladin’s mind thought, accompanied by an excess of phlegm and fevered mumbling at night. Sounds like the grindings.

“Well,” the talkative man said, “perhaps I should ask a di?erent ques tion. Be more speci?c, that’s what my mother always said. Say what you mean and ask for what you want. What’s the story of you getting that ?rst brand of yours?”

Kaladin sat, feeling the wagon thump and roll beneath him. “I killed a lighteyes.”

His unnamed companion whistled again, this time even more apprecia tive than before. “I’m surprised they let you live.”

“Killing the lighteyes isn’t why I was made a slave,” Kaladin said. “It’s the one I didn’t kill that’s the problem.”

“How’s that?”

Kaladin shook his head, then stopped answering the talkative man’s questions. The man eventually wandered to the front of the wagon’s cage and sat down, staring at his bare feet.

•

Hours later, Kaladin still sat in his place, idly ?ngering the glyphs on his forehead. This was his life, day in and day out, riding in these cursed wagons.

His ?rst brands had healed long ago, but the skin around the shash brand was red, irritated, and crusted with scabs. It throbbed, almost like a second heart. It hurt even worse than the burn had when he grabbed the heated handle of a cooking pot as a child.

Lessons drilled into Kaladin by his father whispered in the back of his brain, giving the proper way to care for a burn. Apply a salve to prevent infection, wash once daily. Those memories weren’t a comfort; they were an annoyance. He didn’t have fourleaf sap or lister’s oil; he didn’t even have water for the washing.

The parts of the wound that had scabbed over pulled at his skin, making his forehead feel tight. He could barely pass a few minutes without scrunching up his brow and irritating the wound. He’d grown accustomed to reaching up and wiping away the streaks of blood that trickled from the cracks; his right forearm was smeared with it. If he’d had a mirror, he could probably have spotted tiny red rotspren gathering around the wound.

The sun set in the west, but the wagons kept rolling. Violet Salas peeked over the horizon to the east, seeming hesitant at ?rst, as if making sure the sun had vanished. It was a clear night, and the stars shivered high above. Taln’s Scar—a swath of deep red stars that stood out vibrantly from the twinkling white ones—was high in the sky this season.

That slave who’d been coughing earlier was at it again. A ragged, wet cough. Once, Kaladin would have been quick to go help, but something within him had changed. So many people he’d tried to help were now dead. It seemed to him—irrationally— that the man would be better o? without his interference. After failing Tien, then Dallet and his team, then ten successive groups of slaves, it was hard to ?nd the will to try again.

Two hours past First Moon, Tvlakv ?nally called a halt. His two brutish mercenaries climbed from their places atop their wagons, then moved to build a small ?re. Lanky Taran—the serving boy—tended the chulls. The large crustaceans were nearly as big as wagons themselves. They settled down, pulling into their shells for the night with clawfuls of grain. Soon they were nothing more than three lumps in the darkness, barely distinguishable from boulders. Finally, Tvlakv began checking on the slaves one at a time, giving each a ladle of water, making certain his investments were healthy. Or, at least, as healthy as could be expected for this poor lot.

Tvlakv started with the ?rst wagon, and Kaladin—still sitting—pushed his ?ngers into his makeshift belt, checking on the leaves he’d hidden there. They crackled satisfactorily, the sti?, dried husks rough against his skin. He still wasn’t certain what he was going to do with them. He’d grabbed them on a whim during one of the sessions when he’d been allowed out of the wagon to stretch his legs. He doubted anyone else in the caravan knew how to recognize blackbane—narrow leaves on a trefoil prong—so it hadn’t been too much of a risk.